|

In the first paper of this serial contribution, I have suggested that an interdisciplinary approach that focuses upon attachment experiences and their effects on regulatory structures and functions can offer us more comprehensive models of normal development. This conception directly evolves from the central tenets of attachment theory. In his groundbreaking volume, Attachment , John Bowlby (1969) argued that developmental processes could best be understood as the product of the interaction of a unique genetic endowment with a particular environment. Integrating then current biology with developmental psychoanalytic concepts, he proposed that the infant’s "environment of adaptiveness" has consequences that are "vital to the survival of the species", and that the attachment relationship directly influences the infant’s "capacity to cope with stress" by impacting the maturation of a "control system" in the infant’s brain that comes to regulate attachment functions. From the very start, Bowlby contended that a deeper understanding of the complexities of normal development could only be reached through an integration of developmental psychology, psychoanalysis, biology, and neuroscience (Schore, 2000a).

Over the course of (and since) the "decade of the brain" the amount of scientific information concerning the unique psychological, psychobiological, and neurobiological phenomena that occur in the early stages of human life has rapidly expanded (Schore, 1996, 1997a, 1998a, b, 1999a, 2000b). With an eye to these data, at the end of the very same decade Mary Main proclaimed:

We are now, or will soon be, in a position to begin mapping the relations between individual differences in early attachment experiences and changes in neurochemistry and brain organization. In addition, investigation of physiological "regulators" associated with infant-caregiver interactions could have far-reaching implications for both clinical assessment and intervention (1999, pp. 881-882).

This current confluence of attachment theory, psychobiology, and neurobiology, the one that Bowlby predicted, offers us a real possibility of creating more complex interdisciplinary conceptions of attachment and social and emotional development. The field of infant mental health specifically focuses upon social emotional development, and so more detailed psychoneurobiological understandings of attachment can generate a more overarching model of the normal development of the human mind/brain/body at the earliest stage of the lifespan and therefore more precise definitions of adaptive infant mental health.

With that goal in mind, in the preceding article I have argued that in attachment transactions of affective synchrony, the psychobiologically attuned caregiver interactively regulates the infant’s positive and negative states, thereby co-constructing a growth facilitating environment for the experience-dependent maturation of a control system in the infant’s right brain. The efficent functioning of this coping system is central to the infant’s expanding capacity for self regulation, the ability to flexibly regulate stressful emotional states through interactions with other humans - interactive regulation in interconnected contexts, and without other humans - autoregulation in autonomous contexts. The adaptive capacity to shift between these dual regulatory modes, depending upon the social context, is an indicator of normal social emotional development. In this manner a secure attachment relationship facilitates right brain development, promotes efficient affect regulation, and fosters adaptive infant mental health.

But from the beginning, attachment theory has also had a parallel interest in the etiology of abnormal development. In applying the theory to the links between stress coping failures and psychopathology, Bowlby (1978) proposed:

In the fields of etiology and psychopathology [attachment theory] can be used to frame specific hypotheses which relate different family experiences to different forms of psychiatric disorder and also, possibly, to the neurophysiological changes that accompany them.

These germinal ideas have lead to the field of developmental psychopathology, an interdisciplinary approach that conceptualizes normal and aberrant development in terms of common underlying mechanisms (Cicchetti, 1994). This field is also now incorporating current data from neuroscience into more complex models of psychopathogensis.

This is because contemporary neuroscience is now producing more studies of not just the pathology of the mature brain, but the early developmental failures of the brain. And so neurobiology is currently exploring "early beginnings for adult brain pathology" (Altman, 1997) and describing "alteration[s] in the functional organization of the human brain which can be correlated with the absence of early learning experiences" (Castro-Caldas et al., 1998). These data are also relevant to the field of infant mental health, with its interest in all early conditions that place infants and/or their families at risk for less than optimal development.

These trends indicate that an integration of current attachment theory, neuroscience, and infant psychiatry can offer more complex models of psychopathogenesis (Schore, 1994; 1997d; 1998d). Toward that end, in this second part of this sequential work, I will offer interdisciplinary data in order to strenghthen the theoretical connections between attachment failures, impairments of the early development of the brain’s stress coping systems, and maladaptive infant mental health. And so I will present ideas on the effects of traumatic attachment experiences on the maturation of brain regulatory systems, the neurobiology of relational trauma, the neuropsychology of a disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern, the inhibitory effects of early trauma on the development of control systems involved in affect regulation, the links between early relational trauma and a predisposition to postraumatic stress disorder, a neurobiological model of dissociation, the connections between traumatic attachment and enduring right hemisphere dysfunction, and implications for early intervention.

In the course of this work I will use the disorganized/disoriented ("type D") attachment pattern as a model system of maladaptive infant mental health. This attachment category is found predominantly in infants who are abused or neglected (Carlson, Cicchetti, Barnett, & Braunwald, 1989; Lyons-Ruth, Repacholi, McLeod, & Silva, 1991) and is associated with severe difficulties in stress management and dissociative behavior in later life (van Ijzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakersman-Kranenburg, 1999). In the broadest sense, this work utilizes a psychoneurobiological perspective to attempt to explicate "how external events may impact on intrapsychic structure and development for infants and children already burdened by high psycho-social risk" (Osofsky, Cohen, & Drell, 1995, p. 596). These models are offered as heuristic proposals that can be evaluated by experimental and clinical research.

An Overview of Traumatic Attachments and Brain Development

Development may be conceptualized as the transformation of external into internal regulation. This progression represents an increase of complexity of the maturing brain systems that adaptively regulate the interaction between the developing organism and the social environment. The experiences necessary for this experience-dependent maturation are created within the attachment context, the dyadic regulation of emotions. More specifically, as outlined in the previous paper, the primary caregiver of the securely attached infant affords emotional access to the child and responds appropriately and promptly to his or her positive and negative states. She allows for the interactive generation of high levels of positive affect in co-shared play states, and low levels of negative affect in the interactive repair of social stress, i.e., attachment ruptures.

Because stable attachment bonds are vitally important for the infant's continuing neurobiological development, these dyadically regulated events scaffold an expansion of the child’s coping capacities, and therefore adaptive infant and later adult mental health. In psychobiological research on mother-infant affiliative processes, Kalin, Shelton, and Lynn describe the long-enduring effects of such transactions (1995, pp. 740-741):

The quality of early attachment is known to affect social relationships later in life. Therefore, it is conceivable that the level of opiate activity in a mother and her infant may not only affect behaviors during infancy, but may also affect the development of an individual’s style of engaging and seeking out supportive relationships later in life.

In contrast to this scenario, the abusive caregiver not only shows less play with her infant, she also induces traumatic states of enduring negative affect. Because her attachment is weak, she provides little protection against other potential abusers of the infant, such as the father. This caregiver is inaccessible and reacts to her infant's expressions of emotions and stress inappropriately and/or rejectingly, and shows minimal or unpredictable participation in the various types of arousal regulating processes. Instead of modulating she induces extreme levels of stimulation and arousal, either too high in abuse or too low in neglect, and because she provides no interactive repair the infant’s intense negative emotional states last for long periods of time. Such states are accompanied by severe alterations in the biochemistry of the immature brain, especially in areas associated with the development of the child’s coping capacities (Schore, 1996; 1997a).

There is now agreement that repetitive, sustained emotional abuse is at the core of childhood trauma (O’ Hagan, 1995), and that prenatal maltreatment or neglect compromises cognitive development (Trickett & McBride-Chang, 1995). In line with the established general principle that childhood abuse is a major threat to children’s mental health (Hart & Brassard, 1987), a context of very early relational trauma serves as a matrix for maladaptive infant (and later adult) mental health. Current developmental research is now delving into the most severe forms of attachment disturbances, reactive (Boris & Zeanah, 1999) and disorganized (Lyons-Ruth & Jacobvitz, 1999; Solomon & George, 1999) attachment disorders, and are offering neurobiological models that underlie these early appearing psychopathologies (Hinshaw-Fuselier, Boris, & Zeanah, 1999). Such massive attachment dysfunctions are clearly prime examples of maladaptive infant mental health.

It has been said that "sexual trauma and childhood abuse may simply be the most commonly encountered severely aversive events inherent in our culture" (Sirven & Glasser, 1998, p. 232). Trauma in the first two years, as at any point in the lifespan, can be inflicted upon the individual from the physical or interpersonal environment. It is now established, however, that social stressors are "far more detrimental" than non-social aversive stimuli (Sgoifo et al., 1999). For this reason I will use the term "relational trauma" throughout this work. Because such trauma is typically "ambient," the stress embedded in ongoing relational trauma is therefore not "single-event" but "cumulative." Because attachment status is the product of the infant’s genetically-encoded psychobiological predisposition and the caregiver experience, and attachment mechanisms are expressed throughout later stages of life, early relational trauma has both immediate and long-term effects, including the generation of risk for later-forming psychiatric disorders.

Within the biopsychosocial model of infant psychiatry, the diathesis-stress concept prescribes that psychiatric disorders are caused by a combination of a genetic-constitutional predisposition and environmental or psychosocial stressors that activate the inborn neurophysiological vulnerability. In light of the fact that the brain growth spurt begins in the third trimester in utero (Dobbing & Smart, 1974), genetic-constitutional factors can be negatively impacted during this period by adverse conditions within the uterine maternal-infant environment. For example, very recent research shows that maternal hormones regulate the expression of genes in the fetal brain, and that acute changes in maternal hormone induce changes in gene expression in the fetal brain that are retained when it reaches adulthood (Dowling et al., 2000). Other sudies reveal that high levels of maternal corticotropin-releasing hormone during pregnancy negatively affects fetal brain development (Glynn, Wadhwa, & Sandman, 2000) and reduces later postnatal capacities to respond to stressful challenge (Williams, Hennessey, & Davis, 1995).

These and other data indicate that certain maternal stimuli that impinge upon the fetus negatively impact the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis (Sandman et al., 1994; Glover, 1997; Weinstock, 1997) and thereby produce an enduring neurophysiological vulnerability. There is now convincing evidence of the enduring detrimental effects of maternal alcohol (Streissguth et al., 1994), drug (Jacobson et al., 1996; Espy, Kaufman, & Glisky, 1999), and tobacco (Fergusson, Woodward, & Horwood, 1998) use during pregnancy on the child’s development. These risk factors in part reflect a delay in postnatal brain development (Huppi et al., 1996) which is expressed not only in prematurity and low birth weight, but also in poor infant interactive capacities (Aitken & Trevarthen, 1997). These limitations in social responsiveness may be aligned with parental avoidance or rejection (Field, 1977), and even physical abuse of the premature infant (Hunter et al., 1978).

Various maternal behaviors may severely dysregulate the homeostasis and even future development of the developing fetus, yet these are not usually considered to be instances of trauma. On the other hand, caregiver abuse and neglect of the postnatal infant are viewed as clear examples of relational trauma. Again, in neonatal phases, both genetic factors that influence stress responsivity and detrimental environmental effects interact to contribute to a behavioral outcome, that is stress exaggerates the effects of a developmental lesion (Lipska & Weinberger, 1995). This biopsychosocial model suggests that high risk infants born with delayed brain development and poor interactive capacites, and thereby a vulnerable predisposition, would experience even low levels of relational stress as traumatic, while an infant with a more durable constitution would tolerate higher levels of dyadic misattunement before shifting into dysregulation. There is no one objective threshhold at which all infants initiate a stress response, rather this is subjectively determined and created within a unique organismic-environmental history. Even so, the severe levels of stress associated with infant abuse and neglect are pathogenic to all immature human brains, and the latter maybe even more detrimental to development than the former.

These principles suggest that caregiver-induced trauma is qualitatively and quantitatively more potentially psychopathogenic than any other social or physical stressor (aside from those that directly target the developing brain). In an immature organism with undeveloped and restricted coping capacities, the primary caregiver is the source of the infant’s stress regulation, and therefore sense of safety. When not safety but danger emanates from the attachment relationship, the homeostatic assaults have significant short- and long-term consequences on the maturing psyche and soma. The stress regulating systems that integrate mind and body are a product of developing limbic-autonomic circuits (Rinaman, Levitt, & Card, 2000), and since their maturation is experience-dependent, during their critical period of organization they are vulnerable to relational trauma. Very recent basic research is revealing that perinatal distress leads to a blunting of the stress response in the right (and not left) prefrontal cortex that is manifest in adulthood (Brake, Sullivan, & Gratton, 2000), and that interruptions of early cortical development specifically affect limbic association areas and social behavior (Talamini et al., 1999).

The nascent psychobiological systems that support the primordial motive systems to attach are located in subcortical components of the limbic system. These brainstem neuromodulatory and hypothalamic neuroendocrine systems that regulate the HPA axis are in a critical period of growth pre- and postnatally, and they regulate the maturation of the later-developing cerebral cortex (Bear & Singer, 1986; Schore, 1994; Osterheld-Haas, Van der Loos, & Hornung, 1994; Aitken & Trevarthen, 1997; Durig & Hornung, 2000). Severe attachment problems with the caregiver negatively impact the postnatal development of these biogenic amine systems (Kraemer & Clarke, 1996).

In human infancy, relational trauma, like exposure to inadequate nutrition during the brain growth spurt (Levitsky & Strupp, 1995; Mendez & Adair, 1999), to biological pathogens or chemical agents that target developing brain tissue (Connally & Kvalsvig, 1993), and to physical trauma to the baby’s brain (Anderson et al., 1999), interferes with the experience-dependent maturation of the brain’s coping systems, and therefore have a long-enduring negative impact on the trajectory of developmental processes.

Negative Impact of Relational Trauma on Infant Mental Health

The neuropsychobiological literature underscores a central finding of developmental science - that the maturation of the infant’s brain is experience-dependent, and that these experiences are embedded in the attachment relationship (Schore, 1994, 2000b; Siegel, 1999). If there is truth to the dictum that security of the attachment bond is a primary defense against trauma-induced psychopathology, then what about the infant who doesn’t have such an experience but its antithesis? And since attachment transactions occur in a period in which the brain is massively developing, what is the future course of the brain/mind/body of an infant who does not have the good fortune of engaging with a caregiver who co-creates the child’s internal sense of emotional security? What if the brain is evolving in an environment of not interpersonal security, but danger? Is this a context for the intergenerational transmission of psychopathology, and the origins of maladaptive infant mental health? Will early trauma have lasting consequences for future mental health, in that the trajectory of the developmental process will be altered?

This portrait of infancy is usually not presented by the media, or even in current books on the effects of early experience on brain development (e.g., Bruer, 1999; Gopnik, Meltzoff, & Kuhl, 1999). This is not the image of a "scientist in the crib," but rather of "ghosts in the nursery" (Fraiberg, Adelson, & Shapiro, 1975). In fact, this infant is depicted in Karr-Morse and Wiley’s (1997) Ghosts From the Nursery: Tracing the Roots of Violence. These authors ask, what is the effect of early trauma, abuse and/or neglect, on developing brain anatomy? And how does this effect the future emotional functioning of the individual as he or she passes into the next stages of the lifespan?

In his last work Freud (1940) observed that trauma in early life effects all vulnerable humans because "the ego...is feeble, immature and incapable of resistance." In recent thinking, this dictum translates to the principle that the infant’s immature brain is in a state of rapid development, and is therefore exquisitely vulnerable to early adverse experiences, including adverse social experiences. An entire recent issue of the journal Biological Psychiatry is devoted to development and vulnerability (Foote, 1999), and in it De Bellis et al. present two papers on developmental traumatology and conclude, "the overwhelming stress of maltreatment in childhood is associated with adverse influences on brain development" (1999, p. 1281).

A number of scientific and clinical disciplines are now focusing on not only the interactional aspects of early trauma, but also on the untoward effects of abuse and deprivational neglect on the development of the infant brain. In a major advance of our knowledge, discoveries in the developmental sciences now clearly show that the primary caregiver acts as an external psychobiological regulator of the "experience-dependent" growth of the infant's nervous system (Schore, 1994, 1996, 1997a, 2000c). These early social events are imprinted into the neurobiological structures that are maturing during the brain growth spurt of the first two years of life, and therefore have far-reaching effects. Eisenberg (1995) refers to "the social construction of the human brain," and argues that the cytoarchitectonics of the cerebral cortex are sculpted by input from the social environment. The social environment can positively or negatively modulate the developing brain.

Early relational trauma, which is usually not a singular event but "ambient" and "cumulative," is of course a prime example of the latter. These events may not be so uncommon. In 1995 over 3 million children in this country were reported to have been abused or neglected (Barnet & Barnet, 1998), and the Los Angeles Times reported that in California, in 1997, there were 81,583 reported cases of neglect and 54, 491 reported cases of physical abuse. Although these sources did not specify how many infants were in these categories, other evidence indicates that in the United States the most serious maltreatment occurs to infants under 2 years of age (National Center of Child Abuse and Neglect, 1981). Homicide (Karr-Morse and Wiley, 1997) and traumatic head injury (Colombani et al., 1985) are the leading causes of death for children under 4.

A 1997 issue of Pediatrics contains a study of covert videorecordings of infants hospitalized for life-threatening events, and it documents, in a most careful and disturbing manner, the various forms of child abuse that are inflicted by caregivers on infants as young as 3 months while they are in the hospital (Southall et al., 1997). These experiences are recorded and stored in the infant. Terr (1988, p. 103) has written that "literal mirroring of traumatic events by behavioral memory [can be] established at any age, including infancy." According to Luu and Tucker, "To understand neuropsychological development is to confront the fact that the brain is mutable, such that its structural organization reflects the history of the organism" (1996, p. 297).

Because early abuse negatively impacts the developing brain of these infants, it has enduring effects. There is extensive evidence that trauma in early life impairs the development of the capacities of maintaining interpersonal relationships, coping with stressful stimuli, and regulating emotion. A body of interdisciplinary research demonstrates that the essential experiences that shape the individual’s patterns of coping responses are forged in the emotion-transacting caregiver-infant relationship (Schore, 1994; 2000b). We are now beginning to understand, at a psychobiological level, specifically how beneficial early experiences enhance and detrimental early histories inhibit the development of the brain’s active and passive stress coping mechanisms.

The current explosion of developmental studies are highly relevant to the problem of how early trauma uniquely alters the ongoing maturation of the brain/mind/body. As Gaensbauer and Siegel have written, prolonged and frequent episodes of intense and unregulated interactive stress in infants and toddlers have devastating effects on "the establishment of psychophysiological regulation and the development of stable and trusting attachment relationships in the first year of life" (1995, p. 294). Perhaps even more revealing is the fact that these early dysregulating experiences lead to more than an insecure attachment, they trigger a chaotic alteration of the emotion processing limbic system that is in a critical period of growth in infancy. The limbic system has been suggested to be the site of developmental changes associated with the rise of attachment behaviors (Anders & Zeanah, 1984) and to be centrally involved in the capacity "to adapt to a rapidly changing environment" and in "the organization of new learning" (Mesulam, 1998, p. 1028). These limbic circuits are particularly expressed in the right hemisphere (Tucker, 1992; Joseph, 1996), which is in a growth spurt in the first two years of life (Schore, 1994).

There is now agreement that, in general, the enduring effects of traumatic abuse are due to deviations in the development of patterns of social information processing. I suggest that, in particular, early trauma alters the development of the right brain, the hemisphere that is specialized for the processing of socioemotional information and bodily states. The early maturing right cerebral cortex is dominant for attachment functions (Henry, 1993; Schore, 1994, 2000b, c; Siegel, 1999) and stores an internal working model of the attachment relationship. An enduring developmental impairment of this system would be expressed as a severe limitation of the essential activity of the right hemisphere - the control of vital functions supporting survival and enabling the organism to cope actively and passively with stressors (Wittling & Schweiger, 1993).

Davies and Frawley (1994) describe the immediate effects of parent-inflicted trauma on attachment:

The continued survival of the child is felt to be at risk, because the actuality of the abuse jeopardizes (the) primary object bond and challenges the child’s capacity to trust and, therefore, to securely depend (p. 62).

In contexts of relational trauma the caregiver, in addition to dysregulating the infant, withdraws any repair functions, leaving the infant for long periods in an intensely disruptive psychobiological state that is beyond her immature coping strategies. In studies of a neglect paradigm, Tronick and Weinberg describe:

When infants are not in homeostatic balance or are emotionally dysregulated (e.g., they are distressed), they are at the mercy of these states. Until these states are brought under control, infants must devote all their regulatory resources to reorganizing them. While infants are doing that, they can do nothing else (1997, p. 56).

In other words, infants who experience chronic relational trauma too frequently forfeit potential opportunities for socioemotional learning during critical periods of right brain development.

But there is also a pernicious long-term consequence of relational trauma - an enduring deficit at later points of the life span in the individual’s capacity to assimilate novel (and thus stressful) emotional experiences. At the end of the nineteenth century Janet (1889) speculated:

All [traumatized] patients seem to have the evolution of their lives checked; they are attached to an unsurmountable object. Unable to integrate traumatic memories, they seem to have lost their capacity to assimilate new experiences as well. It is...as if their personality development has stopped at a certain point, and cannot enlarge any more by the addition of new elements.

The functional limitations of such a system are described by Hopkins and Butterworth (1990): "Undifferentiated levels of development show relatively rigid but unstable modes of organization in which the organism cannot adapt responses to marked changes coming from within or without" (p. 9). From a psychoanalytic perspective, Emde (1988) defines pathology as a lack of adaptive capacity, an incapacity to shift strategies in the face of environmental demands. In psychiatric writings, van der Kolk (1996) asserts that under ordinary conditions traumatized individuals adapt fairly well, but they do not repond to stress the way others do, and Bramsen, Dirkzwager, and van der Ploeg observe that in the aftermath of trauma, certain personality traits predispose individuals to engage in less successful coping strategies. All of these all descriptions characterize an immature right brain, the locus of the human stress response (Wittling, 1997).

This structural limitation of the right brain is responsible for the individual’s inability to regulate affect. As van der Kolk and Fisler (1994) have argued, the loss of the ability to regulate the intensity of feelings is the most far-reaching effect of early trauma and neglect. I further suggest that significantly altered early right brain development is reflected in a "type D" (Main & Solomon, 1986) the disorganized/disoriented attachment seen in abused and neglected infants (Carlson et al., 1989; Lyons-Ruth et al., 1991). This severe right brain attachment pathology is involved in the etiologies of a high risk for both posttraumatic stress disorder (Schore, 1997a; 1998c, e; 1999c, d; 2000d) and a predisposition to relational violence (Lyons-Ruth & Jacobvitz, 1999; Schore, 1999b). In discussing the characteristics of toddlers and preschoolers exhibiting severe psychiatric disturbance, Causey, Robertson, and Elam (1998) report that a large number of these young patients were neglected and/or physically or sexually abused. Main (1996) argues that "disorganized" and "organized" forms of insecure attachment are primary risk factors for the development of mental disorders.

The Neurobiology of Infant Trauma

Although the body of studies on childhood trauma is growing, to this date there is still hardly any research on infant trauma. A noteworthy example is the work of Perry and his colleagues, which is extremely valuable because it includes not just behavioral but also developmental neurobiological and psychobiological data. Perry et al. (1995) demonstrate that the human infant’s psychobiological response to trauma is comprised of two separate response patterns, hyperarousal and dissociation. In the initial stage of threat, a startle or alarm reaction is initiated, in which the sympathetic component of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) is suddenly and significantly activated, resulting in increased heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, and muscle tone, as well as hypervigilance. Distress is expressed in crying and then screaming.

In very recent work, this dyadic transaction is described by Beebe as "mutually escalating overarousal" of a disorganized attachment pair:

Each one escalates the ante, as the infant builds to a frantic distress, may scream, and, in this example, finally throws up. In an escalating overarousal pattern, even after extreme distress signals from the infant, such as ninety-degree head aversion, arching away...or screamimg, the mother keeps going (2000, p. 436).

The infant’s state of "frantic distress," or what Perry terms fear-terror is mediated by sympathetic hyperarousal, known as ergotropic arousal (Gellhorn, 1967. It reflects excessive levels of the major stress hormone corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) which regulates catecholamine activity in the sympathetic nervous system (Brown et al., 1982). Noradrenaline is also released from the locus coeruleus (Svensson, 1987; Butler et al., 1990; Aston-Jones et al, 1996). The result is rapid and intensely elevated noradrenaline and adrenaline levels which trigger a hypermetabolic state within the brain. In such "kindling" states (Adamec, 1990; Post et al., 1997), very large amounts of CRF and glutamate, the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain (Chambers et al., 1999), are expressed in the limbic system (Schore, 1997a). Harkness and Tucker (2000) state that early traumatic experiences, such as childhood abuse, literally kindle limbic areas.

But Perry’s group describes a second, later-forming reaction to infant trauma, dissociation, in which the child disengages from stimuli in the external world and an attends to an "internal" world. The child’s dissociation in the midst of terror involves numbing, avoidance, compliance and restricted affect. Traumatized infants are observed to be staring off into space with a glazed look. This behavioral strategy is described by Tronick and Weinberg:

[W]hen infants’ attempts to fail to repair the interaction infants often lose postural control, withdraw, and self-comfort. The disengagement is profound even with this short disruption of the mutual regulatory process and break in intersubjectivity. The infant’s reaction is reminiscent of the withdrawal of Harlow’s isolated monkey or of the infants in institutions observed by Bowlby and Spitz (1997, p. 66).

The state of conservation-withdrawal (Kaufman & Rosenblum, 1967, 1969; Schore, 1994) is a parsympathetic regulatory strategy that occurs in helpless and hopeless stressful situations in which the individual becomes inhibited and strives to avoid attention in order to become "unseen." This state is a primary hypometabolic regulatory process, used throughout the lifespan, in which the stressed individual passively disengages in order "to conserve energies...to foster survival by the risky posture of feigning death, to allow healing of wounds and restitution of depleted resources by immobility" (Powles, 1992, p. 213). It is this parasympathetic mechanism that mediates the "profound detachment" (Barach, 1991) of dissociation. If early trauma is experienced as "psychic catastrophe" (Bion, 1962), dissociation represents "detachment from an unbearable situation" (Mollon, 1996), "the escape when there is no escape" (Putnam, 1997), and "a last resort defensive strategy" (Dixon, 1998).

Most importantly, the neurobiology of the later-forming dissociative reaction is different than the initial hyperarousal response. In this passive state pain numbing and blunting endogenous opiates are elevated. These opioids, especially enkephalins, instantly trigger pain-reducing analgesia and immobility (Fanselow, 1986) and inhibition of cries for help (Kalin, 1993). In addition, the behavior-inhibiting steroid, cortisol is elevated. The inhibition produced by cortisol results from the rapid modulation of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors by cortisol metabolites (Majewska et al., 1986; Orchinik, Murray, & Moore, 1994). GABA is the principal inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain.

Furthermore, vagal tone increases dramatically, decreasing blood pressure and heart rate, despite increases in circulating adrenaline. This increased parasympathetic trophotropic hypoarousal (Gellhorn, 1967) allows the infant to maintain homeostasis in the face of the internal state of sympathetic ergotropic hyperarousal. In the traumatic state, and it may be long-lasting, both the sympathetic energy-expending and parasympathetic energy-conserving components of the infant’s developing ANS are hyperactivated.

In the developing brain states organize neural systems, resulting in enduring traits. That is, traumatic states in infancy trigger psychobiological alterations that effect state-dependent affect, cognition, and behavior. But since they are occurring in a critical period of growth of the emotion regulating limbic system, they negatively impact the experience-dependent maturation of the structural systems that regulate affect, thereby inducing characterological styles of coping that act as traits for regulating stress. In light of the principle that "Critical periods for pathogenic influences might be prolonged in these more slowly maturing systems, of which the prefrontal cortex is exemplary" (Goldberg & Bilder, p. 177), prefrontolimbic areas would be particularly vulnerable. What psychoneurobiological mechanism could account for this?

The brain of an infant who experiences frequent intense attachment disruptions is chronically exposed to states of impaired autonomic homeostasis which he/she shifts into in order to maintain basic metabolic processes for survival. If the caregiver does not participate in stress-reparative functions that reestablish psychobiological equilibrium, the limbic connections in the process of developing are exposed to high levels of excitotoxic neurotransmitters, such as glutamate (Choi, 1992; Moghaddam, 1993) as well as cortisol (Moghaddam et al., 1994; Schore, 1997a) for long periods of time. The neurotoxic effects of glucocorticoids are synergistcally amplified by simultaneous activation of the excitotoxic N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-sensitive glutamate receptor, a critical site of neurotoxicity and synapse elimination in early development (McDonald, Silverstein, & Johnston, 1988; Guilarte, 1998).

It is known that stress-induced increases of glucocorticoids in postnatal periods selectively induce neuronal cell death in "affective centers" in the limbic system (Kathol et al., 1989), imprint an abnormal limbic circuitry (Benes, 1994), and produce permanent functional impairments of the directing of emotion into adaptive channels (DeKosky, Nonneman, & Scheff, 1982). The interaction between corticosteroids and excitatory transmitters is now thought to mediate programmed cell death and to represent a primary etiological mechanism for the pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric disorders (Margolis, Chuang, & Post, 1994). Here is a template for impaired limbic morphogenesis, a structural alteration which will reduce future adaptive coping functions. This is a context for psychopathogenesis.

The major environmental influence on the development of the limbic structures involved in organismic coping is the attachment relationship. Severe disruption of attachment bonds in infancy leads to a regulatory failure expressed in disturbances in limbic activity, hypothalamic dysfunction, and impaired autonomic homeostasis (Reite & Capitanio, 1985). The dysregulating events of abuse and neglect produce extreme and rapid alterations of ANS sympathetic ergotropic hyperarousal and parasympathetic trophotropic hypoarousal that create chaotic biochemical alterations, a toxic neurochemistry in the developing brain.

The neurochemistry of brain growth is essentially regulated by the monoaminergic neuromodulators, especially the biogenic amines dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin, and the neuropeptide and steroid neurohormones. In critical periods, increased production of these agents, many of which are trophic, are matched by increased production of the receptors of such agents. Prenatal stress is known to alter biogenic amine levels on a long-lasting basis (Schneider et al., 1998). Postnatal traumatic stress also induces excessive levels of dopamine, activating excitatory NMDA receptor binding of glutamate (Knapp, Schmidt, & Dowling, 1990). Excitatory neurotransmitters regulate postsynaptic calcium influx in developing neocortex (Yuste & Katz, 1991) and glutamate acting at NMDA receptors increases intracellular calcium in neurons (Burgoyne, Pearce, & Cambray-Deakin, 1988), which, if uncontrolled, leads to intracelluar damage or cell death (Garthwaite & Garthwaite, 1986).

In other words, intense relational stress alters calcium metabolism in the infant’s brain, a critical mechanism of cell death (Farber, 1981). Dopamine (Filloux & Townsend, 1993; McLaughlin et al., 1998) and glutamate (Tan et al., 1998) can be neurotoxic, by generating superoxide free radicals associated with oxidative stress (Lafon-Cazal, Pietri, Culcas, & Bockaert, 1993), especially hydroxyl radicals which destroy cell membranes (Lohr, 1991). These events greatly enhance "apoptotic" or "programmed cell death" (Margolis et al., 1994; Schore, 1997a). During a critical period of growth of a particular brain region, DNA production is highly increased, and so excitotoxic stress, which is known to cause oxidative damage to DNA, lipid membrane, and protein (Liu et al., 1996), also negatively impacts the genetic systems within evolving limbic areas.

Indeed, there is now evidence to show that adverse social experiences during early critical periods result in permanent alterations in opiate, corticosteroid, corticotropin releasing factor, dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin receptors (Coplan et al., 1996; Ladd et al., 1996; Lewis et al., 1990; Martin et al., 1991; Rosenblum et al., 1994; van der Kolk, 1987). Such receptor alterations are a central mechanism by which "early adverse developmental experiences may leave behind a permanent physiological reactivity in limbic areas of the brain" (Post, Weiss, & Leverich, 1994, p. 800).

It is now established that "dissociation at the time of exposure to extreme stress appears to signal the invocation of neural mechanisms that result in long-term alterations in brain functioning" (Chambers et al., 1999, p. 274). In other words, infants who experience states of terror and dissociation and little interactive repair, especially those with a genetic-constitutional predisposition and an inborn neurophysiological vulnerability, are high risk for developing severe psychopathologies at later stages of life. Bowlby asserted,

since much of the development and organization of [attachment] behavioral systems takes place whilst the individual is immature, there are plenty of occasions when an atypical environment can divert them from developing on an adaptive course (1969, p. 130).

Recall, attachment involves limbic imprinting, and so infant trauma will interfere with the critical period organization of the limbic system, and therefore impair the individual’s future capacity to adapt to a rapidly changing environment and to organize new learning (Mesulam, 1998). Maladaptive infant mental health is therefore highly correlated with maladaptive adult mental health.

The infant posttraumatic stress disorder of hyperarousal and dissociation thus sets the template for later childhood, adolescent, and adult posttraumatic stress disorders (PTSD), all of which show disturbances of autonomic arousal (Prins, Kaloupek, & Keane, 1995) and abnormal catecholaminergic function (Southwick et al., 1993). In each, "chronic, inescapable or uncontrollable stress may lead to impairment of the normal counter-regulatory mechanisms producing hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and sympathetic nervous systems, which could lead to excessive anxiety, feelings of hopelessness and defeat, and depression" (Weinstock, 1997, p. 1). The latter symptomatic triad represents unregulated parasympathetic activity that is associated with dissociation. At any point of the lifespan, dissociative defensive reactions are elicited almost instantaneously.

This continuity in infant and adult coping deficits is described by Nijenhuis, Vanderlinden, and Spinhoven (1998):

The stress responses exhibited by infants are the product of an immature brain processing threat stimuli and producing appropriate responses, while the adult who exhibits infantile responses has a mature brain that, barring stress-related abnormalities in brain development, is capable of exhibiting adult response patterns. However, there is evidence that the adult brain may regress to an infantile state when it is confronted with severe stress (pp. 253).

But, as we have seen, developmental neurobiological studies now demonstrate that "the overwhelming stress of maltreatment in childhood is associated with adverse influences on brain development" (De Bellis et al. 1999, p. 1281), and that "early adverse experiences result in an increased sensitivity to the effects of stress later in life and render an individual vulnerable to stress-related psychiatric disorders" (Graham et al., 1999, p. 545).

The Neuropsychology and Neuropsychoanalysis of a Disorganized / Disorriented Attachment Pattern

The next question is, how would the trauma-induced psychobiological and neurobiological alterations of the developing brain be expressed in the behavior of an early traumatized toddler? We have the data. In a classic study, Main and Solomon (1986) studied the attachment patterns of infant’s who had suffered trauma in the first year of life. This lead to the discovery of a new attachment category, "type D", an insecure-disorganized / disoriented pattern. [This work is updated and summarized by Solomon and George (1999) in a recent volume, Attachment Disorganization].

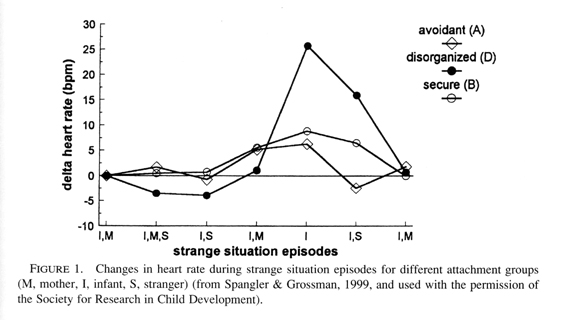

The "type D" pattern is found in over 80% of maltreated infants (Carlson et al., 1989). Indeed Spangler and Grossman (1999) demonstrate that this group of toddlers exhibits the highest heart rate activation and most intense alarm reaction in the strange situation procedure (see Figure 1). They also show higher cortisol levels than all other attachment classifications and are at greatest risk for impaired hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis stress responding (Hertsgaard et al., 1995). Main and Solomon conclude that "these infants are experiencing low stress tolerance" (1986, p. 107). These authors contend that the disorganization and disorientation reflect the fact that the infant, instead of finding a haven of safety in the relationship, is alarmed by the parent. They note that because the infant inevitably seeks the parent when alarmed, any parental behavior that directly alarms an infant should place it in an irresolvable paradox in which it can neither approach, shift its attention, or flee. At the most basic level, these infants are unable to generate a coherent behavioral coping strategy to deal with this emotional challenge.

|

Main and Solomon documented, in some detail, the uniquely disturbing behaviors these 12-month-old infants show in Strange Situation reunion transactions. These episodes of interruptions of organized behavior and low stress tolerance are often brief, frequently lasting 10-30 seconds, yet they are highly significant. For example, they show a simultaneous display of contradictory behavior patterns, such as "backing" towards the parent rather than approaching face-to-face.

The impression in each case was that approach movements were continually being inhibited and held back through simultaneous activation of avoidant tendencies. In most cases, however, proximity-seeking sufficiently "over-rode" avoidance to permit the increase in physical proximity. Thus, contradictory patterns were activated but were not mutually inhibited (Main & Solomon, 1986, p. 117).

Notice the simultaneous activation of the energy expending sympathetic and energy conserving parasympathetic components of the ANS.

Maltreated infants also show evidence of apprehension and confusion, as well as very rapid shits of state during the stress inducing Strange Situation.

One infant hunched her upper body and shoulders at hearing her mother’s call, then broke into extravagent laugh-like screeches with an excited forward movement. Her braying laughter became a cry and distress-face without a new intake of breath as the infant hunched forward. Then suddenly she became silent, blank and dazed (Main & Solomon, 1986, p. 119).

A dictionary definition of apprehension is distrust or dread with regard to the future. These apprehensive behaviors generalize beyond just interactions with the mother. The intensity of the baby’s dysregulated affective state is often heightened when the infant is exposed to the added stress of an unfamiliar person. At a stranger’s entrance, two infants moved away from both mother and stranger to face the wall, and another "leaned forehead against the wall for several seconds, looking back in apparent terror" (Main & Solomon, 1986).

These maltreated infants also showed "behavioral stilling" - that is, "dazed" behavior and depressed affect (again a hyperactivation of the PNS). One infant "became for a moment excessively still, staring into space as though completely out of contact with self, environment, and parent" (p. 120) Another showed "a dazed facial appearance...accompanied by a stilling of all body movement, and sometimes a freezing of limbs which had been in motion". And yet another "fell face-down on the floor in a depressed posture prior to separation, stilling all body movements".

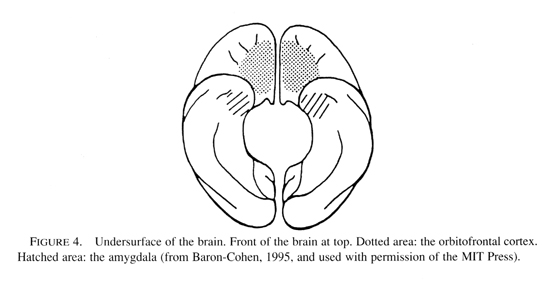

Furthermore, Main and Solomon point out that the type "D" behaviors take the form of stereotypies that are found in neurologically impaired infants. It should be emphasized that these behaviors are overt manifestations of an obviously impaired regulatory system, one that rapidly disorganizes under stress. Notice that these observations are taking place at 12 to 18 months, a critical period of corticolimbic maturation, and they reflect a severe structural impairment of the orbitofrontal control system that is involved in attachment behavior and state regulation. The orbitofrontal areas, like other limbic structures in the anterior temporal areas and the amygdala, contains neurons that fire to emotionally expressive faces. The mother’s face is the most potent visual stimulus in the child’s world, and it is well known that direct gaze can mediate powerful aggressive messages.

During the trauma, the infant is presented with an aggressive expression on the mother’s face. The image of this aggressive face, as well as the chaotic alterations in the infant’s bodily state that are associated with it, is indelibly imprinted into subcortical limbic circuits as a "flashbulb memory" (Brown & Kulik, 1977) and thereby stored in implicit-procedural memory in the visuospatial right hemisphere. These are stored memories of what Lieberman (1997) calls "negative maternal attributions" that contain an intensely negative affective charge, and therefore rapidly dysregulate the infant.

In the course of the traumatic interaction, the infant is presented with another affectively overwhelming facial expression, a maternal expression of fear-terror. Main and Solomon note that this occurs when the mother withdraws from the infant as though the infant were the source of the alarm, and they report that dissociated, trancelike, and fearful behavior is observed in parents of type "D" infants. Current studies show a link between frightening maternal behavior and disorganized infant attachment (Schuengel, Bakersmans-Kranenburg, & Van Ijzendoorn, 1999). I suggest that during these episodes the infant is matching the rhythmic structures of the mother’s dysregulated states, and that this synchronization is registered in the firing patterns of the stress-sensitive corticolimbic regions of the infant’s brain that are in a critical period of growth. This is the context of the down-loading of programs of psychopathogenesis.

Mothers of children with disorganized attachment describe themselves as unable to care for or protect their infants, inflicting harsh punishments, feeling depressed, and being out of control. In general, high risk and physically abusive mothers, relative to comparison mothers, differ in the types of perceptions, attributions, evaluations, and expectations of their children’s behavior, engage in fewer interactions and communicate less with their children, use fewer positive parenting behaviors, and use more aversive disciplinary techniques, (Nayak & Milner, 1998). Role reversal (Mayseless, 1998) and a subjective feeling of helplessness (George & Solomon, 1996) are commonly found mothers of disorganized infants. In light of the fact that many of these mothers have suffered from unresolved trauma themselves (Famularo, Kinscherff, & Fenton, 1992), this spatiotemporal imprinting of the chaotic alterations of the mother’s dysregulated state may be a central mechanism for the "intergenerational transmission child abuse" (Kaufman & Zigler, 1989).

Current research on the neurobiology of attachment is revealing that the early experiences of female infants with their mothers (or absence of these experiences) influence how they respond to their own infants when they later become mothers, and that this provides a psychobiological mechanism for the intergenerational transmission of adaptive and maladaptive parenting styles and responsiveness (Fleming, O’Day, & Kraemer, 1999). This psychobiological principle is advanced in the very recent clinical writings of Silverman and Lieberman, who conclude that although the mother’s caregiving system has an instinctual basis, it is expressed through the filter of her own representational templates, "which derive from her sense of being cared and protected in her relationship with her own parents" (1999, p. 172). This experience did not occur in the abusive mother’s early attachment.

In the latest biosocial model of the determinants of motherhood, Pryce (1995) views parenting as varying on a continuum between the extremes of maximal care and infant/abuse and neglect. Expanding upon these ideas, Maestripieri (1999) asserts that although models of parenting are often presented in terms of social and cognitive processes, recent biological studies in primates of the neurobiological regulation of parental responsivess and the determinants of infant abuse indicate that human parenting is much more sensitive to neuroendocrine mechanisms than previously thought. He portrays maximal parental care, as represented in a mother

...with a genotype for a secure and sensitive personality, a developmental environment that included a secure attachment to an adequate caregiver and experience of ‘play-mothering,’ a stress-free pregnancy and postpartum period, optimal neurobiological priming and control, and considerable social support. Such a female will be highly attracted to her infant and made anxious by its crying, but will not averse to her infant or its novelty per se (Maestripieri, 1999, p. 417).

In contrast, the mother characterized as expressing minimal parental care and maximal neglect presents

...with a genotype for a insecure...personality, a developmental environment that included a insecure attachment to a caregiver and no experience with infants, a stressful pregnancy and postpartum period, a suboptimal neurobiological priming and control, and little or no social support. Such a female will be weakly attracted to her infant and will be averse to the infant, including its crying, its physical burden, and its novelty (Maestripieri, 1999, p. 417).

Maestripieri also suggests that high vulnerability to stress and emotional disorders are common among abusive parents.

Indeed, a vulnerability to dissociation in the postpartum period has been reported by Moleman, van der Hart, and van der Kolk (1992). In a number of cases they describe women panic-striken with the anticipation of losing their babies:

Panic ceased when they dissociated from both their subjective physical experience and from contact with their surroundings. They all continued to experience dissociative phenomena, intrusive recollections about some aspects of the delivery, and amnesia about others, and they all failed to attach to their children (1992, p. 271, my italics).

These symptoms lasted months after the delivery. Notice the authors contention that maternal dissociation blocks infant attachment.

What would be the effect if the mother’s dissociative episodes continued as a clinical depression well through the first year of the infant’s life? I suggest that in certain critical stressful dyadic moments, this same individual will show a vulnerability for a suboptimal neurobiological priming in the form of dissociation. In light of the fact that infant cries produce elevated physiological reactivity and high levels of negative affect in abusing mothers (Frodi & Lamb, 1980), episodes of "persistent crying" (Papousek & von Hofacker, 1998) may be a potent trigger of dissociation. The caregiver’s entrance into a dissociative state represents the real-time manifestation of neglect. Such a context of an emotionally unavailable, dissociating, unresolved/disorganized mother and a disorganized/disoriented infant is evocatively captured by Fraiberg, who provides a painfully vivid description of a dissociative mother and her child’s detachment:

The mother had been grudgingly parented by relatives after her mother’s postpartum attempted suicide and had been sexually abused by her father and cousin. During a testing session, her baby begins to cry. It is a hoarse, eerie cry...On tape, we see the baby in the mother’s arms screaming hopelessly; she does not turn to her mother for comfort. The mother looks distant, self-absorbed. She makes an absent gesture to comfort the baby, then gives up. She looks away. The sceaming continues for five dreadful minutes. In the background we hear Mrs. Adelson’s voice, gently encoraging the mother. ‘What do you do to comfort Mary when she cries like this?’ (The mother) murmurs something inaudible...As we watched this tape later...we said to each other incredulously, ‘It’s as if this mother doesn’t hear her baby’s cries (Fraiberg, cited in Barach, 1991, p. 119).

Ultimately, the child will transition out of hyperexcitation-protest into hyperinhibition-detachment, and with the termination of protest (screaming), she’ll become silent. She will shift out of the hyperarousal, and she’ll dissociate and match the mother’s state. This regulatory failure is experienced as a discontinuity in what Kestenberg (1985) refers to as dead spots in the infant's subjective experience, an operational definition of the restriction of consciousness of dissociation. Winnicott (1958) holds that a particular failure of the maternal holding environment causes a discontinuity in the baby’s need for going-on-being, and that this is a central factor in psychopathogensis. And so not just trauma but the infant’s posttraumatic response to the relational trauma, the parasympathetic regulatory strategy of dissociation, is built into the personality.

There is a long tradition in the classical psychoanalytic literature of the severely detrimental effects of the traumatic effects of a sudden and unexpected influx of massive external stimulation (sympathetic hyperexcitation) that breaches the infant’s stimulus barrier (Freud, 1920) and precludes successful self-regulation (Freud, 1926). This has lead to an emphasis of the role of overstimulation and annihilation anxieties in classical, object relational, and self psychological models of trauma. I suggest that "screaming hopelessly" is the vocal expression of annihilation anxiety, the threat to one’s bodily wholeness and survival, the annihilation of one’s core being.

However, Freud also described the psychic helplessness associated with the ego’s immaturity in the first years of childhood, and postulated that the passively experienced re-emergence of the trauma is "a recognized, remembered, expected situation of helplessness." (1926, p. 166). In writings on psychic trauma and "emotional surrender" Anna Freud (1951/1968; 1964/1969) also referred to helplessness, defined as a state of "disorientation and powerlessness" that the organism experiences in the traumatic moment. Although almost all psychoanalytic theoreticicans have overlooked or undervalued this, Krystal (1988) and Hurvich (1989) emphasize that at the level of psychic survival helplessness constitutes the first basic danger. This helplessness is an early appearing primitive organismic defense against the growth inhibiting effects of maternal over- or understimulation.

What has been undetermined in this literature is how, as Mahler (1958) states, trauma interferes with psychic structure formation. This question can only be answered with reference to current neurobiological models of developing psychic structure. Translating this into developmental neurobiological concepts, evidence now shows that the neurobiological alterations of traumatic sympathetic hyperexcitation and parasympathetic hyperinhibition on the developing limbic system are profound. Perry state that sympathetically-driven early terror states lead to a "sensitized" hyperarousal response. Due to the alterations of maturing catecholamine systems, "critical physiological, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral functions which are mediated by these systems will become sensitized". According to these authors,

Everyday stressors that previously may not have elicited any response now elicit an exaggerated reactivity...This is due to the fact that...the child is in a persisting fear state (which is now a "trait"). Furthermore, this means that the child will very easily be moved from being mildly anxious to feeling threatened to being terrorized (Perry et al., 1995, p. 278).

Thus, not only is the onset of sympathetically driven fear-alarm states more rapid, but their offset is prolonged, and they endure for longer periods of time. This permanent dysregulation of CRF-driven fear states is described by Heim and Nemeroff, who on the basis of a study of adult survivors of childhood abuse suggest that "stress early in life results in a persistent sensitization of these CRF circuits to even mild stress in adulthood, forming the basis for mood and anxiety disoders" (1999, p. 1518).

But, in addition, due to the chaotic parasympathetic alterations that accompany trauma to the early self, this branch of the ANS also is dysregulated. Deprivation of early maternal stress modulation is known to trigger not only an exaggerated release of corticosteroids upon exposure to novel experiences, but, in addition, inhibitory states that persist for longer periods of time. The result is a quicker access into and a longer duration of dissociated states at later points of stress. This represents a deficit, since adaptive coping is reflected by a the termination of a stress response at an appropriate time in order to prevent an excessive reaction (Weinstock, 1997).

Sroufe and his colleagues conclude that early more so than later trauma has a greater impact on the development of dissociation. They write, "The vulnerable self will be more likely to adopt dissociation as a coping mechanism because it does not have either the belief in worthiness gained from a loving and responsive early relationship or the normal level of defenses and integration that such a belief affords" (Ogawa et al., 1997, p. 875).

Critical Period Trauma and Deficient Orbitofrontal Connectivity

In an editorial of a special issue of Biological Psychiatry , Foote writes, "Combining developmental and affective approaches, it may even be possible to test hypotheses regarding the components of stress and affective circuitry that can exhibit dysregulation following traumatic and/or harmful events, especially early in life" (1999, p. 1457). A developmental perspective can tell us when adverse experiences have the greatest disorganizing impact on evolving adaptive functions, and a neurobiological approach can give us clues as to which limbic circuits that mediate these functions are in a critical period of growth, and therefore most vulnerable. Clearly, attachment neurobiology is centrally involved. This leads to the question, specifically what brain systems involved in attachment are negatively impacted by early abuse and neglect?

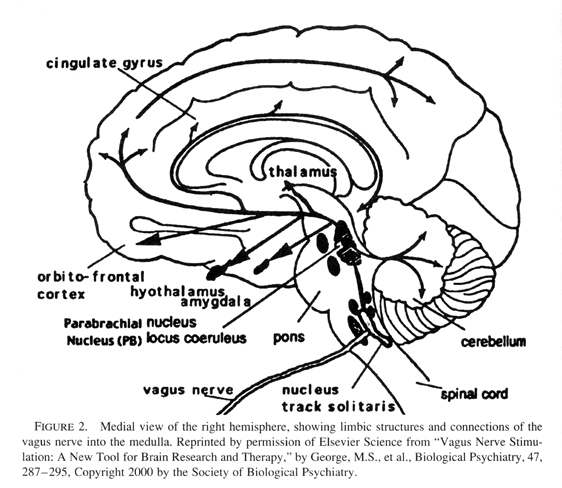

Relational trauma in the first through third quarters of the first year negatively impacts the experience-dependent maturation of the amygdala and anterior cingulate limbic circuits (see previous article). But by the end of this year and into the second, the higher corticolimbic circuits are in a critical period of growth, and therefore negatively impacted. Referring back to Main and Solomon’s studies, these involved infants of 12 to 18 months, a time when internal working models of the attachment relationship are first assessed by the Strange Situation. Research documents that disorganized infant attachment strategies increase in frequency from 12 to 18 months (Lyons-Ruth, Alpern, & Repacholi, 1993). In fact this interval is a critical period for the experience-dependent maturation of the orbitofrontal areas of the cortex (see Figure 2).

|

Perry et al. (1995) contend that early traumatic environments that induce atypical patterns of neural activity interfere with the organization of cortical-limbic areas and compromise, in particular, such brain-mediated functions as attachment, empathy, and affect regulation. These very same functions are mediated by the frontolimbic areas of the cortex, and because of their dysfunction, affective disturbances are a hallmark of early trauma. Teicher (1996) reports that children with early physical and sexual abuse show EEG abnormalities in frontotemporal and anterior brain regions. Teicher concludes that stress alters the development of the prefrontal cortex, arrests its development, and prevents it from reaching a full adult capacity. So the next question is, what kind of psychoneurobiological mechanism could account for this prefrontal developmental arrest?

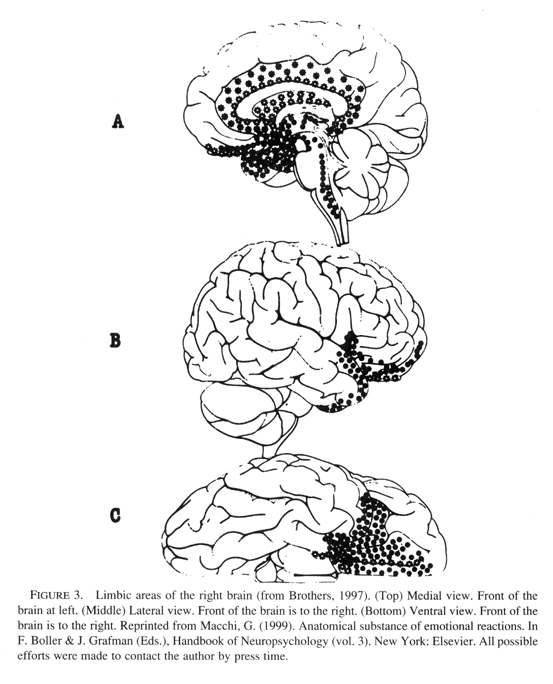

The developing infant is maximally vulnerable to nonoptimal and growth-inhibiting environmental events during the period of most rapid brain growth. During these critical periods of intense synapse production, the organism is sensitive to conditions in the external environment, and if these are outside the normal range a permanent arrest of development occurs. In the previous paper I proposed that the amygdala, anterior cingulate, and insula limbic structures play a role in pre-attachment experiences that onset early in the first year, and thus trauma during each of their critical periods would interfere with the experience-dependent maturation of these limbic structures (see Figure 3).

|

Indeed, neurobiological studies indicate that damage to the amygdala in early infancy is accompanied by profound changes in the formation of social bonds and emotionality (Bachevalier, 1994). These socioemotional effects are long-lasting and appear even to increase in magnitude over time (Malkova et al., 1997). Abnormalities of the social functions of the amygdala are implicated in autism (Baron-Cohen et al., (2000), and this would include autistic posttraumatic developmental disorder (Reid, 1999), a sub-group of children in which trauma in the first two years of life precipitates autism. Even more specifically to the model outlined here, abnormally large right (and not left) amygdala volumes have been reported in children and adolescents with generalized anxiety disorders (de Bellis et al., 2000a).

Relational traumatic events in the middle of the first year act as a growth inhibiting environment for the anterior cingulate limbic network. This would interfere with the ongoing development of the infant’s coping systems, since impairments in anterior cingulate functions are known to lead to prolonged glucocorticoid and ACTH release during stress (Diorio, Viau, & Meaney, 1993) and later deficits in emotional arousal and an impoverished conscious experience of emotion (Lane et al., 1997). Indeed, maltreated children diagnosed with PTSD manifest metabolic abnormaliites of the anterior cingulate (de Bellis, Keshavan, Spencer, & Hall, 2000b). And early relational trauma which interferes with the experience-dependent maturation of the insula negatively impacts its role in generating an image of one’s physical state (body image), a process that underlies the experiencing of basic emotions (Craig et al., 2000).

But in addition, abuse and/or neglect over the first two years negatively impacts the major regulatory system in the human brain, the orbital prefrontolimbic system. In classic basic research, Kling and Steklis (1976) found that orbitofrontal lesions critically disrupt behaviors of "social bonding." More recently, Damasio’s group reports that early neurological damage of this prefrontal cortex caused a failure "to acquire complex social knowledge during the regular developmental period" and an enduring impairment of social and moral behavior due to a "disruption of the systems that hold covert, emotionally related knowledge of social situations" (Anderson et al., 1999, p. 1035). Interestingly, a 20 year-old female patient, who at 15 months sustained ventromedial prefrontal damage due to a car accident, was unable to experience empathy, and "her maternal behavior was marked by dangerous insensitivity to (her) infant’s needs" (p. 1032).

In these cases damage to the orbitofrontal system is of neurological causation. It should be pointed out that relational trauma may be accompanied by physical trauma to not only the body (Southall et al., 1997) but to the developing brain. In either case, the developmental trajectory of the brain’s regulatory systems are negatively altered. In other words failures of structural development occur in relational trauma that includes or does not include physical trauma to the brain. In human infancy, purely "psychological" relational trauma leads to altered brain development, and purely "neurological" trauma negatively impacts relational development. Indeed, "type D" behaviors are found in neurologically impaired infants (Barnett et al., 1999), and infants who experience perinatal complications show orbitofrontal dysfunction in adolescence (Kinney et al., 2000). Sapolsky has pointed out that exposure to acute of chronic stress may be associated with either psychological disorders (such as child abuse) or neurological disorders (Moghaddam et al., 1994).

Earlier, I suggested that physical trauma to the baby’s head and brain have a long-enduring negative impact on the trajectory of developmental processes. Infant/toddler abuse in the form of violent shaking of the head or forceful impact to the skull are sources of traumatic brain injury. The potential for such catastrophic outcomes of relational trauma may increase as the toddler becomes ambulatory in the second year, and account for the increase of "type D" attachments at this time. Although direct studies of such relationally induced brain injuries have not been done, information about the deleterious effects on brain function can be extrapolated from two sources, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) human studies of closed head injuries (Mamelak, 2000), and animal studies of traumatic brain injuries (McIntosh et al., 1989; Gennarelli, 1994). This research may give a model of the metabolic dysregulation occurring within the orbitofrontal areas of a physically traumatized infant/toddler.

Due to the topography of the brain as it sits within the bony skull, orbitofrontal contusions on the ventral surface are particularly common following impact-type closed head injury (Adams et al., 1980). Studies of the biomechanics of traumatic head injury in mature humans demonstrate that the sudden forceful movement of the brain within the skull causes inertial strain and tissue deformation that are greatest at the orbital surfaces of the frontal and temporal lobes, and that these areas are common sites of contusion (Mamelak, 2000). The ensuing anatomical and functional damage occurs whether or not there is impact on the skull or loss of consciousness. The response to orbitofrontal injury is a sudden increase in metabolic energy utilization followed by a prolonged period of metabolic energy depression.

Parallel studies in animal models demonstrate that the neurochemical consequences of closed-head injury occur even without signs of gross morphologic damage. This profile shows an initial significant rise in extracellular levels of excitatory amino acids, glutamate and aspartate, which trigger an initial hypermetabolic response. This in turn elevates intracellular calcium levels, which may last for days, and leads to a prolonged posttraumatic depression. This pattern of initial hypermetabolism followed by hypometabolism (Yoshino et al., 1991) is identical to that described by Perry. The later shut down of cerebral metabolism has been suggested to be due to the action of a sensor in the dorsal medullary region that functions as an energy conservation system which protects the brain against the detrimental consequences of energy depletion (Pazdernik, Cross, & Nelson, 1994).

It has recently been suggested that the symptoms of cerebral physical trauma take the form of a change in emotional functions, personality, and indeed psychiatric disorders, and can be explained as consequences of the impairment of specifically orbitofrontal functions (Mamelak, 2000). As mentioned earlier, Anderson et al. (1999) document the enduring psychosocial deficits that result from orbitofrontal damage (car accident and tumor resection) in the first and second year. These studies of orbitofrontal injury in infancy and adulthood suggest a similar pattern of impairments of energy metabolism in response to both intense physical and psychosocial stressors. The developing brain, which requires large amounts of energy during the brain growth spurt, reacts with massive bioenergetic alterations in response to traumatic assaults of brain and/or body. What would be the common outcome of either physical trauma or relational trauma-induced energy impairments during a critical period of energy-dependent growth of corticolimbic systems?

The postnatal organization of the brain and the progressive postnatal assembly of limbic-autonomic circuits (Rinaman et al., 2000) occurs in a very specific pattern. During a critical period of regional brain growth, genetic factors are expressed in an initial overproduction of synapses. This is followed by a process that is environmentally-driven, the pruning and maintenance of synaptic connections and the organization of functional circuits. This process of genetic-environmental organization of a brain region is energy dependent (Schore, 1994; 1997a; 2000c), and can be altered, especially during its critical period of growth. The construct of developmental instability (Moller & Swaddle, 1997) has been invoked to describe the imprecise expression of the genetic plan for development due to genetic (e.g., mutations) and environmental effects (e.g., toxins). I suggest that the psychotoxic contexts of early relational trauma acts as an inducer of developmental instability, which has been shown to contribute to alterations of cerebral lateralization (Yeo et al., 1997a) and to a vulnerability factor in the etiology of neurodevelopmental disorders (Yeo et al., 1997b).

In a very recent magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1 H-MRS) study of the right frontal lobe, Yeo et al. (2000) conclude that developmental instability

...may lead to a greater need for energy-requiring, stabilizing forces in development. Hence, there may be less in the way of metabolic resources left for metabolic growth (p. 155).

These very same conditions are produced in the patterns of initial hypermetabolism followed by enduring hypometabolism of relational trauma described earlier. This disruption of energy resources for the biosynthesis of right lateralized limbic connections would be expressed in a critical period developmental overpruning of the corticolimbic system, especially one that contains a genetically-encoded underproduction of synapses. This psychopathomorphogentic mechanism acts a generator of high risk conditions.

It is now accepted that "psychological" factors "prune" or "sculpt" neural networks in specifically the postnatal frontal, limbic, and temporal cortices (Carlson, Earls, & Todd, 1988). I propose that excessive pruning of cortical-subcortical limbic-autonomic circuits occurs in early histories of trauma and neglect, and that this severe growth impairment represents the mechanism of the genesis of a developmental structural defect. Since this defect is in limbic organization, the resulting functional deficit will specifically be in the individual’s maturing stress coping systems. The dysregulating events of abuse and neglect create chaotic biochemical alterations in the infant brain, a condition that intensifies the normal process of apoptotic programmed cell death. Post and his colleagues report a study of infant mammals entitled, "Maternal deprivation induces cell death" (Zhang et al,. 1997). Maternal neglect is the behavioral manifestation of maternal deprivation, and this alone or in combination with paternal physical abuse is devastating to developing limbic subsystems.

In its critical period the orbitofrontal areas are synaptically connecting with other areas of the cerebral cortex, but they are also forging contacts with subcortical areas. And so the orbitofrontal cortex is a "convergence zone" where cortex and subcortex meet. In earlier writings I have proposed that it is the severe parcellation (excessive pruning) of hierarchical cortical-subcortical circuits that is central to the developmental origins of the regulatory deficits that are the sequelae of early trauma (Schore, 1997a). Caregiver-induced trauma exacerbates extensive destruction of synapses in this "Senior Executive" of limbic arousal (Joseph, 1996) which directly connects into the dopaminergic and noradrenergic systems in the anterior and caudal reticular formation. Exposure to fear cues provokes enhanced dopamine metabolism in the ventral tegmental areas (Deutsch et al., 1991) which activates the locus coeruleus (Deutsch, Goldstein, & Roth, 1986) and increases noradrenaline activty (Tanaka et al., 1990; Clarke et al., 1996). Both catecholamines are released in response to stressful disruptions of the attachment bond, and elevated levels of these bioamines result in regression of synapses and programmed cell death (McLaughlin et al., 1998; see Schore 1994 and 1997a for a description of dopaminergic disruptions of mitochonrial energy metabolism).

The mechanism of this parcellation, the activity-dependent winnowing of surplus circuitry, has been previously described in terms of hyperactivation of the dopamine-sensitive excitotoxic NMDA-sensitive glutamate receptor, a critical site of synapse neurotoxicity and elimination during early development. As opposed to this hypermetabolic response, cortisol release triggers hypometabolism, a condition that enhances the toxicity of excitatory neurotransmitters (Novelli , Reilly, Lysko, & Henneberry, 1988). During critical periods, dendritic spines, potential points of connection with other neurons, are particularly vulnerable to long pulses of glutamate (Segal, Korkotian, & Murphy, 2000) that trigger severely altered calcium metabolism and therefore "oxidative stress" and apoptotic damage (Park, Bateman, & Goldberg, 1996; Schore, 1997a). It is known that stress causes oxidative damage to brain lipid membranes, protein, and DNA (Liu et al., 1996), including mitochondrial DNA (Bowling et al., 1993; Schinder, Olson, & Montal, 1996; Schore, 1997a), that stress increases levels of excitatory amino acids such as glutamate in the prefrontal cortex (Moghaddam, 1993), and that excitotoxins can destroy orbitofrontal neurons (Dias et al., 1996).